Keeping safe in a dangerous industry

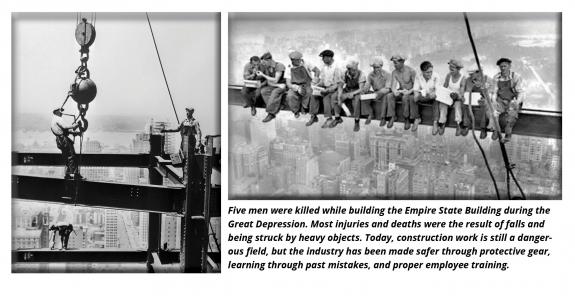

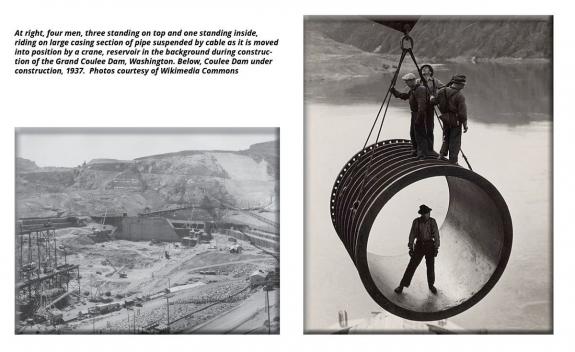

Construction work can be unquestionably dangerous. Its extreme hazards have been captured in iconic images of people working at impossible heights and precarious positions in structures such as the Empire State Building and the Brooklyn Bridge.

Few harnesses or hard hats appear in these historic photos, but the introduction of better safety equipment isn’t the only way that the construction industry has learned from the lessons of the past. Safety is now built in from the start — from the design stages to construction — and teams work together to create a safety culture into everything they do. At the University of Washington, this collaborative approach has led to an accident rate on public work capital projects that is one-third of the state average.

Capital projects at the University are supervised by the Project Delivery Group (PDG) within UW Facilities. Safety concerns get raised not just from leadership but from frontline staff, says PDG’s Mark Sweeters, construction manager for the Hans Rosling Center for Population Health.

“We’re asking things such as ‘are we using the correct tools for the job,’ ‘what kinds of lifts should we be using,’ and ‘how we’re going to best keep workers safe,’” says Sweeters, who has worked at the University for 33 years. “Environmental Health & Safety also reviews the work plans. Safety isn’t a negotiation."

“We also care that the people working here take pride in their jobs,” he says. “The contractors maintain multi-trade safety teams and walk job sites and encourage people to say something if they see anything that might be unsafe.”

Troy Stahlecker, PDG’s director of major capital projects, says the construction industry itself is moving into a collaborative and integrated approach, ultimately making things safer.

“Safety inside and outside the fence”

“Safety inside and outside the fence”

With collaboration comes a better understanding of how the sophisticated building maintenance and operations will be handled in the future, a process referred to as T20.

“Our team shares tremendous pride in safety culture and we take it seriously, as our livelihood depends on it,” Stahlecker adds.

Jeannie Natta, senior project manager with PDG, concurs. “Safety inside and outside the fence and through the duration of the job is what we strive to do,” Natta says. “The workers inside the fence need to be safe just as much as our students and staff all around campus work sites.”

Historically, most construction fatalities were caused by falls and hazardous conditions. While the dangers don’t change and there’s always a high risk of injury, it’s vitally important to learn from the past, says UW Facilities’ Ron Fouty, who has worked 43 years in the safety field.

“Most injuries are predictable. If you can predict it, you can prevent it,” says Fouty, who was safety director for the UW’s Capital Projects Office between 2002 and 2017 and now works part-time for UW Facilities. (A portion of the Capital Projects Office became the Project Delivery Group and joined UW Facilities in 2019.)

“It takes a focused, concentrated effort to prevent accidents,” says UW Facilities Safety Director Tracey Mosier, who has worked at the UW for 31 years. “Like gardening, it requires constant vigilance.” Safety culture also means encouraging workers who incorporate safety concepts into their daily tasks to also take the concept home with them, says Mosier. “Be safe, not just at work, but at home, too.”

Building in safety

Building in safety

Collaboration is also important when it comes to designing safety into buildings from the beginning. Prevention through design (PtD) is an integrated design and construction approach for preventing occupational hazards early in the design process.

Throughout design development, architects, mechanical and electrical consultants, maintenance, operations and UW safety representatives meet to determine how to make a building that is safer both to build and to operate and maintain.

“We’re building safety into the design of things,” says PDG Senior Construction Manager Steve Babinec. “For instance, we’re trying to decide where and how light fixtures are installed so they can be safely reached for lamp replacement, how to install HVAC equipment in ceiling spaces so that it can be serviced safely, any equipment or building components that will require routine service should be installed so that it can be accessed safely.”

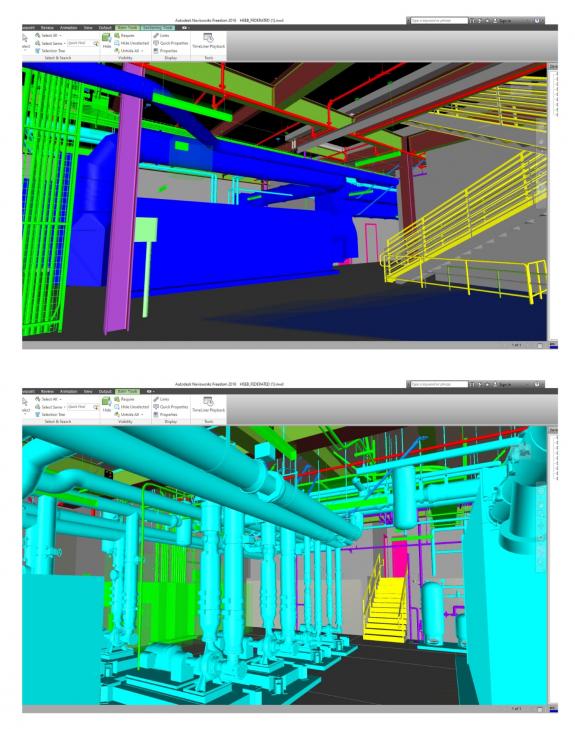

Building Information Modeling software also helps by allowing maintenance and operations staff to see what things will look like, Babinec says. “Potential hazards are identified so that they can be avoided and eliminated.”

This kind of 3D-modeling has been used on many recent projects on campus including the Kincaid Hall Renovation project, and it is currently being used for the Health Sciences Education Building, set for completion in 2022.

Measure twice, cut once

Measure twice, cut once

Slips and falls, cuts to the fingers and hands, back and muscle strains, and being struck by falling objects or debris are still among the most common ways workers get hurt, but incidents on UW’s public work capital projects are much lower than the state average.

The total recordable incident rate (TRIR) is calculated by multiplying the number of safety incidents by 200,000, then dividing that by the total number of hours worked in the year. The higher the rate, the worse the safety record. For example, a TRIR of 4 means there are 4 recordable injuries for every 100 full time workers. As of 2019, the total recordable incident rate for construction in Washington state was 5.7. At the University of Washington, the TRIR for public work capital projects was 1.98 in 2020 and 1.23 in 2019.

Project Delivery Group Executive Director Steve Tatge says that the level of injury that used to be considered acceptable has changed, with the UW setting safety goals that exceed the state average.

“We’ve long had a goal of having our TRIR be below 2.0,” says Tatge, “meaning 2 recordable incidents per 100 workers working full time for a year. “It took a number of years to get there, but we’re consistently at or below 2.0 now. That’s a point of pride for us and something we all work hard to make even better.”

The current collaborative approach which has shown so much success has its roots in work started by former Capital Projects Associate Vice President Richard Chapman. Babinec, Fouty and other longtime staff members credit Chapman, who retired in 2015, for bringing together construction and project managers to talk about safety and insisting that on-the-job injuries be documented. Chapman also established relationships with construction company representatives and required them to have a dedicated safety point person.

Building on this early work, Facilities staff and contractors have worked to continually improve construction safety. Tatge says that a firm’s safety record is one of the criteria the UW uses when selecting building firms.

Lessons learned

Lessons learned

Larry Turney is a superintendent at Skanska USA Building Inc., which recently completed renovation of the Kincaid Hall project. He says Skanska teaches safety to all workers. “Every person has the right to say, stop! If something does not look right or feel right then something is not right! We get together and reevaluate what we are doing and make sure it is safe to do.”

Of course, COVID-19 raised safety protocols and standards to a new level.

“The whole job site had to make changes including allowing only one person in the elevator at a time,” Turney says. “We had to bring in a person whose sole job was to disinfect high traffic areas and take temperatures of every person that came on site. We had a couple close calls but we never had to shut down for fear of an outbreak. Really it was about good and clear communication."

Jeff Cook, the superintendent of the Foster School of Business’s Founders Hall project, also firmly believes in “being safe for safety’s sake.” Cook, who works for Hoffman Construction Company, emphasizes that open communication, personal accountability and learning from previous mishaps all help keep safety top of mind.

“We want our crew to arrive home safely just as they arrived to work safely,” he says.

Safety culture is also a lesson that UW interns learn and then take with them into the industry. Harkarn Bains interned with the Project Delivery Group from 2018 to 2020. Now a project engineer with VECA Electric, Bains recalls of his time at the UW, “There was no slack when it came to safety. Whether that was the PDG staff, our contractors, our clients, the student body, or campus visitors, safety was the number one priority.”

What other advice does Fouty, the 40+ year safety veteran/expert have?

“The best way to influence peoples’ behavior is to really engage folks in personal, genuine conversations,” Fouty says. “You need to talk directly about and to staff and if someone gets injured, we need to talk about that. And never rest on your safety laurels.”

Interested in safety at the UW? Join the EH&S Newsletter mailing list by adding your UWNetID and clicking "Enter this group" to receive health and safety updates. UWNetID is required to access the mailing list.