Beyond the cherry trees

The UW's Seattle campus is home to 570 species of trees. Mark Stone/University of Washington

The Yoshino cherry trees in the Quad draw thousands of people to campus every spring, but they are just one of the jewels that make up the campus tree canopy.

The University of Washington has about 570 species of trees on the Seattle campus, making it home to more varieties than just about any other American college or university, says UW Facilities gardener Theo Hoss. Hoss, who is also working on a master’s degree in natural resources at Oregon State University, has led tours of the UW’s campus trees for the last four years.

His involvement with UW trees began when he was an undergraduate in 2020. He answered a listing from the UW School of Environmental and Forest Sciences to update the Brockman Memorial Tree Tour, created by forestry Professor Frank Brockman in 1980 to showcase 81 UW trees.

But many of the trees had been removed and the tour needed a refresh. So Hoss and fellow student Thuy Luu launched a new website, with entries to replace the out-of-date ones. Hoss then further expanded on Professor Brockman’s vision by leading monthly in-person tours, publicizing them on social media and installing informational tags with QR codes on the trees.

The UW’s care and stewardship of its trees earned it recognition from the Arbor Foundation as a Tree Campus USA in 2024 for the 14th time.

As an expert on UW trees, Hoss shared some other trees that you might want to check out when visiting campus this spring.

Most interesting

Most interesting

Monkey puzzle tree

Hoss said when he’s giving a tour, he always gets a question about the monkey puzzle tree on Denny Yard, the lawn between Denny Hall and the Quad. It happens “even if we're on the opposite side of campus, even if we're not stopping at it.”

The monkey puzzle tree is the object of fascination due to its unique look, with its pointy leaves that spiral down its graceful branches. There are no other trees like it, because it doesn’t grow natively in the northern hemisphere. The tree’s lineage dates back to 190 million years ago and is part of a family that now only exists in places that were part of the ancient continent of Gondwana, which includes Antarctica, South America, Africa and Australia.

“The main field of thought around its really funky looking leaves,” Hoss said, “is that they've evolved to look that way, to respond to pressures from the environment that we don't have anymore. They're designed by nature to try to avoid being eaten by dinosaurs.”

Most historic to the University

Most historic to the University

English elm

The three trees standing in a line are remnants of the original oval design for campus. The English elm stands to the right of the walking path. Misty Shock Rule

Three trees on Denny Yard run parallel to the front of the hall, one of them a tall English Elm. They are remnants of the original design of the University, which was a giant oval stretching to Parrington, Lewis and Clark Halls and facing a central lawn. That space later became the Quad.

”That design never finished playing out, but they kind of started doing the landscaping for it,” Hoss said. “So this is one of the places on campus that you do see some of the oldest trees we have left.” There are no trees left that predate the University’s move from downtown in 1895.

English elms were planted frequently in U.S. cities in the late 1800s and early 1900s due to their height and narrow canopy. The species has been largely wiped out due to Dutch Elm disease, which the University’s trees are protected from due to the close monitoring of the UW grounds team and frequent fungicide treatments.

“It's fairly unique to be able to find such large elm trees in this area,” said Hoss. “I've seen them spotted around the city, but not in the concentration that we have here at the University.”

Most historic to the United States

Most historic to the United States

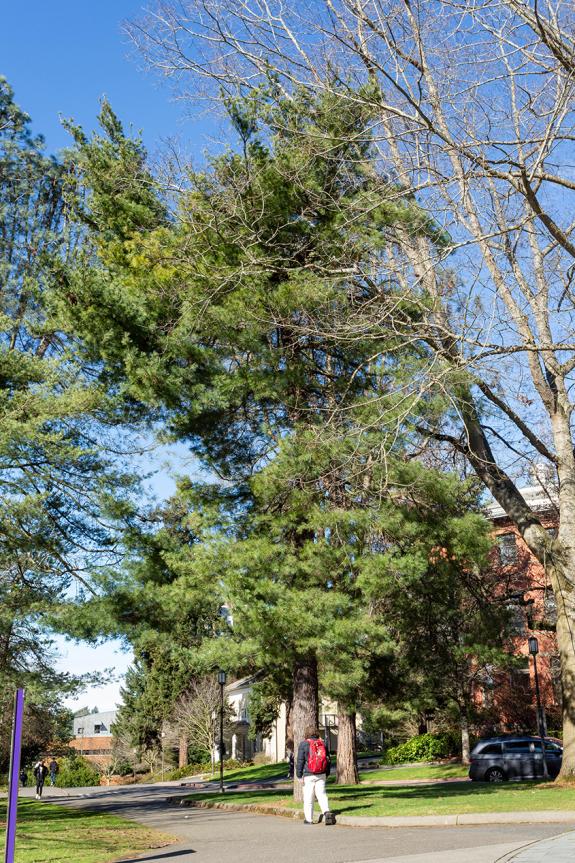

Eastern white pine

At the edge of Red Square, behind Odegaard Undergraduate Library and west of the flagpole, stand two Eastern white pine trees. “A little known piece of American history is that this species — actually the conflict over their ownership — led to what could reasonably be seen as the first incident of rioting in the colonies against the British government,” Hoss said.

The tree, which is native to the Northeast, Midwest and Appalachia, was prized for its straight trunk and other properties that made it ideal as material for ship masts.

By the time the British colonized America, they had decimated their own forests. Recognizing the value of the Eastern white pines, the king claimed ownership of all trees of that species and of a certain size, marking them with three slashes shaped like an arrow.

Colonists were forbidden from cutting down the tree, and those who did were fined. When the crown started taking harsher action and jailed some who violated the law, the colonists fought back in an event known as the Pine Tree Riot, which took place in Weare, N.H., in April 1772, foreshadowing the Boston Tea Party.

Tallest tree

Tallest tree

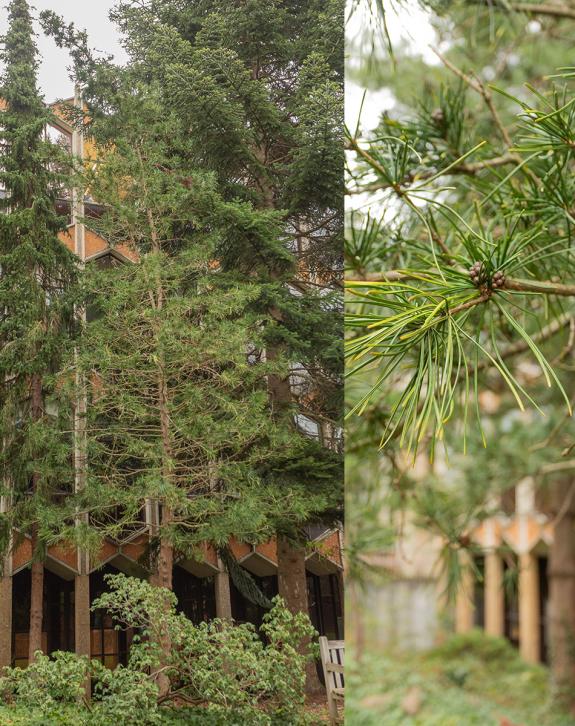

Douglas-fir

The Douglas-fir in Heron's Haven south of Drumheller Fountain stands tallest over its neighbors. Misty Shock Rule

Hoss can attest to the tallest tree personally. “I measured all the contenders myself last spring,” he said. The prize goes to a Douglas-fir located in a spot known as Heron Haven, a wedge-shaped urban forest that sits between Anderson Hall, the Chemistry Building and Rainier Vista.

The tree, which is 126 feet tall, may not look impressive at first sight. “At its base, it’s not more than a few feet across,” Hoss said. “But if you take a step back and look at it from Rainier Vista, you can really see it climbing above everything else growing there.”

Heron Haven is so named because of the Great Blue Heron rookery that was sited there. In 2019, students with the Society for Ecological Restoration UW cleaned up the space, which had been overrun by ivy and other invasive species. With funding from the Campus Sustainability Fund, the group planted native species, installed a path and bench, and took other actions to improve the area’s ecological integrity.

Around the time when restoration started, bald eagles chased off the herons. Hoss said that while herons no longer nest there, you can see bald eagles fairly often.

Hidden gem

Hidden gem

Japanese umbrella pine

Between Sieg Hall and Allen Library, you’ll find a tree that is one of its kind on campus and unusual to find in Seattle, unless you go to a Japanese garden. The Japanese umbrella pine, like the monkey puzzle tree, has a lineage that stretches back 100 million years.

It’s not a pine even though it is named as one, evolving millions of years before pines did. And it has another surprising trait: Its needles are not leaves, despite their appearance.

“They're actually evolved out of out of sticks on the tree instead of from the material that most leaves on trees are made out of,” said. Hoss. “And it just has, in my opinion, one of the most graceful forms of trees that you can find on campus. They're kind of bunched up at the tips, and it looks really whimsical.”

Favorite tree

Favorite tree

Sugar pine

For Hoss, choosing a favorite tree on campus is really difficult. But he has an affinity for trees that remind him of home in California. He points to the sugar pine on the edge of Parrington Lawn. The species grows in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California and the Cascades in Oregon.

The sugar pine is one of the tallest pine tree species in the world. It also has one of the longest pinecones in the world, measuring up to two feet in length. The cones are “one of those charismatic features that makes people stop and go, ‘Holy cow, look at this thing that I just found on the ground here,’” Hoss said.

Located near a path where people enter campus from 15th Ave. NE, the sugar pine is also a tree that Hoss walked by almost every day when he lived in the U District. “It just has this beautiful, elegant, drooping look to it,” he said.