Oh baby, baby it's a wild world

On a sunny June afternoon, UW Facilities employee Jennell Taylor was at her computer when something outside caught her eye in the greenspace between the Facilities Administration Building and Stevens Way.

Where the wild things are

Where the wild things are

“It sniffed around the perimeter of the lawn and trotted out of sight toward the UW Club,” says Taylor. “I ran outside and watched it slink into the shrubbery. I lost sight of the creature until it emerged onto the sidewalk. An equally surprised student stopped me to ask if he’d really just seen a coyote. We watched as it continued north along the sidewalk in front of Hall Health, where it abruptly changed course and, hilariously, used the crosswalk to the HUB. A driver even stopped to let it cross. I’m used to seeing them in the country, but this is the first in-city sighting I’ve ever had.”

”Coyotes have been around campus for quite some time, says Howard Nakase, manager of Facilities Grounds, but says that daytime sightings are now more frequent. “They are actually more afraid of humans than we should be of them. They also have been keeping our rodent population in check, so they are an essential part of our campus ecosystem.”

Christopher Schell, an assistant professor of urban ecology at UW Tacoma who studies coyote behavior says he’s not surprised that coyotes have been spotted on campus. He’s currently working with Laura Prugh, an associate professor at UW’s Seattle campus, on a coyote boldness study, to see if they become bolder over time in cities.

“Urban systems are ripe for coyote colonization, primarily due to the fact that there are so many abundant resources and there aren’t any legitimate competitors,” Schell says. “In less disturbed habitats, coyotes would have to vie for their place among carnivores with clear size advantages. In cities, that pressure is released.”

UW student Jane Jones took the video, at right, of a campus coyote behind McMahon Hall at 6:45 a.m on May 14.

In mixed company

In mixed company

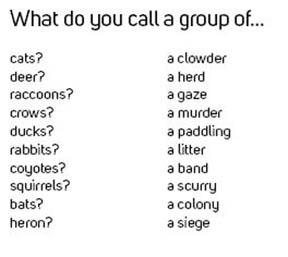

Coyotes aren’t the only wildlife who call campus home, of course. UW Facilities installs a duck ramp at Drumheller Fountain every spring to help make way for ducklings. And Facilities staff, who often work early and late, encounter other animals all the time.

“I’ve seen a lot of stuff over the decade I’ve worked here,” says maintenance mechanic Dale Lyman, whose days begin at 6 a.m. He says he sees raccoons and rabbits nearly every day and has photographed deer in the Quad and on the HUB lawn.

Gardener Keith Possee spends most of his time tending to the Medicinal Herb Garden, where eastern cottontail rabbits have been grazing for the last five years or so. The species is the most common rabbit in North America as well as on campus, and sports a brown coat and a short, fluffy white tail.

“I've been using hardware cloth barriers to protect the plants as soon as the first damage appears,” Possee says. “Staying ahead of the rabbits is an ongoing process.”

He says he sees all sorts of animals and birds every day, and maintains a blog about his visitors, including great blue heron, bald eagles, ducks and raccoons.

"Unfortunately, so many people now spend so much time staring at their smart phones that they miss a lot.”

Prugh, the associate professor of environmental and forest sciences who studies coyote behavior and who teaches Wildlife Techniques, says that her students calculated rabbit density estimates in the Union Bay Natural Area were twice as high in 2019 as they were in 2017.

“The students hypothesized rabbit abundance would have declined with the removal of lots of Himalayan blackberry, [a highly invasive weed that provides good coverage for rabbits] but they appear to be doing quite well,” Prugh says.

Urban wildlife

Urban wildlife

You’d have to look very hard these days to find cats gallivanting about, though. That’s because through much effort, says Sharon Talbert, who founded Friends of Campus Cats in 1988, the number of feral cats has dwindled from more than 100 in the late 1980s to just a handful. While the organization still exists, Talbert retired from her campus job and now fosters and socializes wild cats closer to her own neighborhood. But she says if a stray cat or kitten is found on campus, she’d gladly make a house call.

Conversely, the campus squirrel population appears to be thriving. The eastern gray squirrel is the species you’ll most likely spot from virtually any vantage point. Jim Kenagy, a UW professor emeritus of biology, says they survive well in urban environments because they’re opportunistic in their behavior and they can subsist on a variety of fare — some natural (tree bark, seeds, berries) and some less healthy (discarded pizza, bagels, French fries).

“The only real predators for squirrels on our campus are the tires of automobiles,” says Kenagy.

If you see an injured or dead squirrel — or any other injured, sick or dead animal — please report them to Environmental Health & Safety (EH&S) at 206-616-1623 or 206-543-7209. Contact Facilities’ Customer Care Team at careteam@uw.edu or 206-685-1900 to report other pests.

Not all wildlife on the UW campus is of the four-legged kind. Charles Easterberg, a lecturer who spent more than four decades working for EH&S, says he’s dealt with ant infestations and helped move birds’ nests from interior locations. If it’s a pest and unwanted, he’s dealt with it.

And speaking of birds, we’d be remiss if we didn’t consult national crow expert and UW Professor of Forest Sciences, John Marzluff, for this article. Marzluff considers bird life on campus to be “outstanding.”

That is, “One can easily see 40-50 species in a day of birding from main campus through the Montlake Fill [Union Bay Natural Area] and into the Arboretum,” he says. “While the campus habitats have changed a lot since the early 1900’s, our recent survey of birds indicates that the diversity of birds on campus has increased since that time.”

And while Marzluff is clearly enamored by crows, not everyone is a fan.

Ed Kromer, an employee in the Foster School of Business, says while he finds them a nuisance, he holds no ill will.

“I admire their intelligence but I don’t trust them. I feel like they sometimes squawk aggressively when I pass too close to their offspring. They may be organizing.”

Kromer’s suspicions may not be far-fetched.

Adds Marzluff, “Crows, for example, are known to recognize individual people and work some for regular handouts. But be careful, if you get on a crow’s wrong side they can hold grudges for a lifetime!”