Where did the leaves go?

Mike Erickson starts to rake out a batch of leaves collected from the University of Washington campus in Seattle, Wash. on Oct. 23, 2015. The leaves will be used to make compost for the University’s grounds.

In the fall, the crunch is all too familiar.

As breezes rattle campus trees, leaves unlatch themselves from the branches, drifting down onto brick pathways and grassy fields.

But when January rolls around, the sound of the crunch disappears, as if it never existed.

So where do the leaves go?

Past the golf driving range is a pile of leafs – but not just any ordinary stack. These leaves are piled high: shorter than a semi-truck, but taller than your average college student. The stack is crumpled by footsteps, worn by the weather, and damp from the rainy season. The leaves are also sifted together with coffee grounds. Not great for leaf-jumping.

The compost yard sits near the Environmental Safety Storage Building in Seattle, Wash. on Oct. 23, 2015. The compost yard was funded by the Campus Sustainability Fund. The leaves are collected sifted in with coffee grounds to create the final compost product, which is distributed across campus gardens.

The leaves raked up underneath an old family oak are no comparison. After all, backyard leaves aren’t usually prepared into compost.

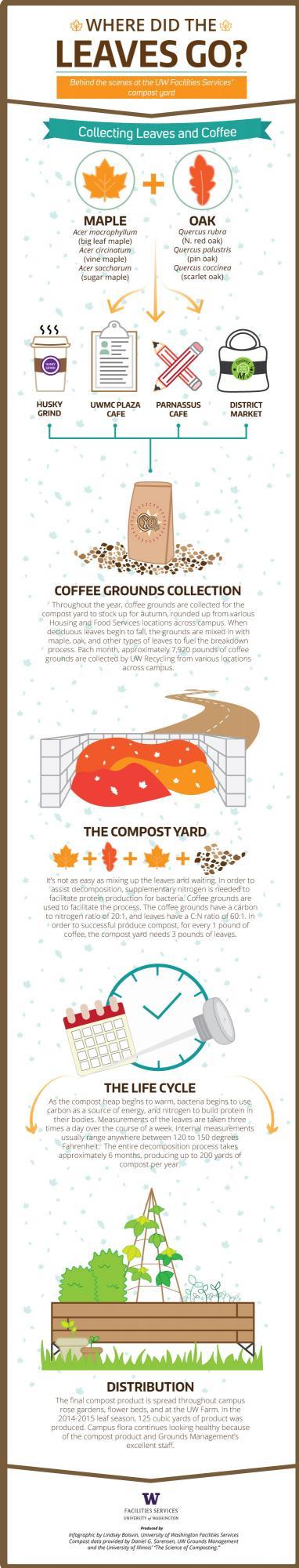

The compost yard – a UW Grounds Management project – was first up and running in the 2013-2014 school year thanks to the Campus Sustainability Fund. The facility was constructed in 2013, with oak, maple, and other types of leaves filling the yard, and coffee grounds littered across the pavement.

Grounds Management requested over $75,000 in funds from the CSF in 2011-2012 to implement the program. The goal was to localize the compost process to the UW campus, and create a more sustainable method of distributing the finished product.

In the past, an environmental solutions company named Cedar Grove accepted the University’s leaves and converted them into compost product. The University would then buy back the product that would be sprinkled in the University’s rose gardens and flower beds.

To reduce transportation emissions and slash additional costs, the compost yard blossomed, and found its home across near the Environmental Health and Safety office building.

It all begins when the first batch of leaves are collected.

Hundreds of deciduous trees are planted across campus, meaning thousands of leaves fall in autumn.

Grounds Management staff and heavy equipment operators scour the pathways to deliver leaves to the compost yard. The leaves are collected by blowers, street sweepers, or are raked up by hand. The piles – stuffed into the back of trucks and garbage cans – are driven down the hill to the compost yard.

But every batch isn’t alike.

The street sweeper – a clunky machine with circular, spinning “feather dusters” – doesn’t have a trash filter. When plastic bags, empty bottles, and red solo cups are tossed into the road, they can get diverted into the leaf heap. To combat this, Grounds Management only uses leaves from the sweeper from less-traveled paths.

“There were definitely lessons learned last year,” said Daniel Sorensen, the sustainability coordinator for Grounds Management. Sorensen has been working closely with the program to ensure its success. It’s been a trial-and-error process.

The yard itself is big and blocky, but even it can’t hold the entirety of the campuses’ leaves.

On site, there is 250 cubic yards for production, which can yield anywhere from 150-200 yards of compost per year.

“At this point, we have enough [compost] to go around,” Sorensen said.

Leaf season, usually starting in October and lasting until December or January, is just one part of the equation.

Summer, autumn, winter, and spring all share something in common: people are buying coffee.

The smell wafts through cafeterias, kitchenettes, and cafes. Housing and Food Services provides students with coffee in a variety of locations throughout campus, from the basement of the art building to the District Market.

In a joint effort with Grounds Management, UW Recycling collects the coffee grounds around campus to transport them to the compost yard.

Why are coffee grounds so important? One word: nitrogen.

When the conditions are right, decomposers take over the leaf pile. Aerobic bacteria is responsible for most of the breakdown. Microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, alter the chemistry of organic wastes.

According to the University of Illinois, “Bacteria utilizes carbon as a source of energy (to keep on eating) and nitrogen to build protein in their bodies (so they can grow and reproduce).”

Macroorganisms, such as slugs, centipedes, beetles, and ants, wiggle their way into the yard to grind down leafs and other materials. Composting isn’t just a combine-and-wait game. The entire process has multiple, intertwined facets.

The oxidation process, temperature changes, acidity levels, and moisture points can all impact the final product. The processes that fuel decomposition can also halt the process if circumstances are too severe. For example, if there isn’t enough air circulation, microorganisms that warm up the pile can wither away.

It’s all about the perfect balance.

So while the coffee is being collected throughout the year – nearly 8,000 pounds of it per month – the leaves are being dumped and turned in the compost yard.

In the back of a truck on a hazy October day, Greg Moe a gardener from area 1 backed his truck toward the heavy pile, slow and steady. His back tires got right up to the edge, not quite far enough to crunch the leaves.

Moe flipped the switch: the bed of the truck began to tip. It went higher and higher into the air, dumping at a 45 degree angle, then upwards to 70 degrees. Moe got into the truck and drove, the leaves tumbling out into the compost yard as he went.

Moe has worked the University for over 20 years. He’s seen the changes, and he noticed the collection process has gotten more efficient over time.

“As far as hauling leaves, it has been a little bit easier on the shoulders,” Moe said.

Moe turned off the truck, the truck bed completely level now. He walked to the back of the vehicle, brushing off the remaining leaves, his hands covered by gloves.

Another truck pulled in soon after, carrying more leaves and two passengers: Mike Erickson and Jessie Heasley.

Erickson and Heasley, also campus gardeners, repeated the same emptying process, tipping the truck bed toward the pile. They raked out the remainder, scratching at the truck. Erickson then walked into mass of leaves carrying a metal rod.

The rod, which Erickson described as, “like a meat thermometer – a really long stick,” measures the internal temperature of the compost pile.

Erickson was the one who had the initial idea for developing an on-campus compost process. His idea for the compost pile began the entire project.

Internal readings usually read anywhere between 120-150 degrees. The heat indicates the composting process is working: bacteria is forming, eating away at the leaves.

Just a few steps from the yard, there was a pile of finished compost.

Sorensen leaned over and reached into the pile, picking up a clump in his right hand.

The finished product is a sixth month process, and the product of efforts by Grounds Management to localize the process on campus.

The future of the compost yard looks bright, and not just because of the orange and yellow leaves.

Grounds Management is looking at new methods to make the most out of the yard. Investing in new tools could help assist the process. With the purchase of a leaf shredder, the compost yard could hold more product, thus producing more compost for the gardeners to distribute across campus.

“I think it’s a marvel how you can up with something like that. You’d never know [the compost] was leaves,” Erickson said.

Daniel Sorensen, the sustainability coordinator for Grounds Management, holds out a pile of leaves and coffee grounds scooped up from the compost yard in Seattle, Wash. on Oct. 23, 2015.